Note: This is a companion piece, of sorts, to this and this. It is loosely based on my time as the general manager of a fine dining restaurant in an upscale suburb, but by no means are any of the characters in this story based on real people. Names and other details have been changed to protect me from litigation.

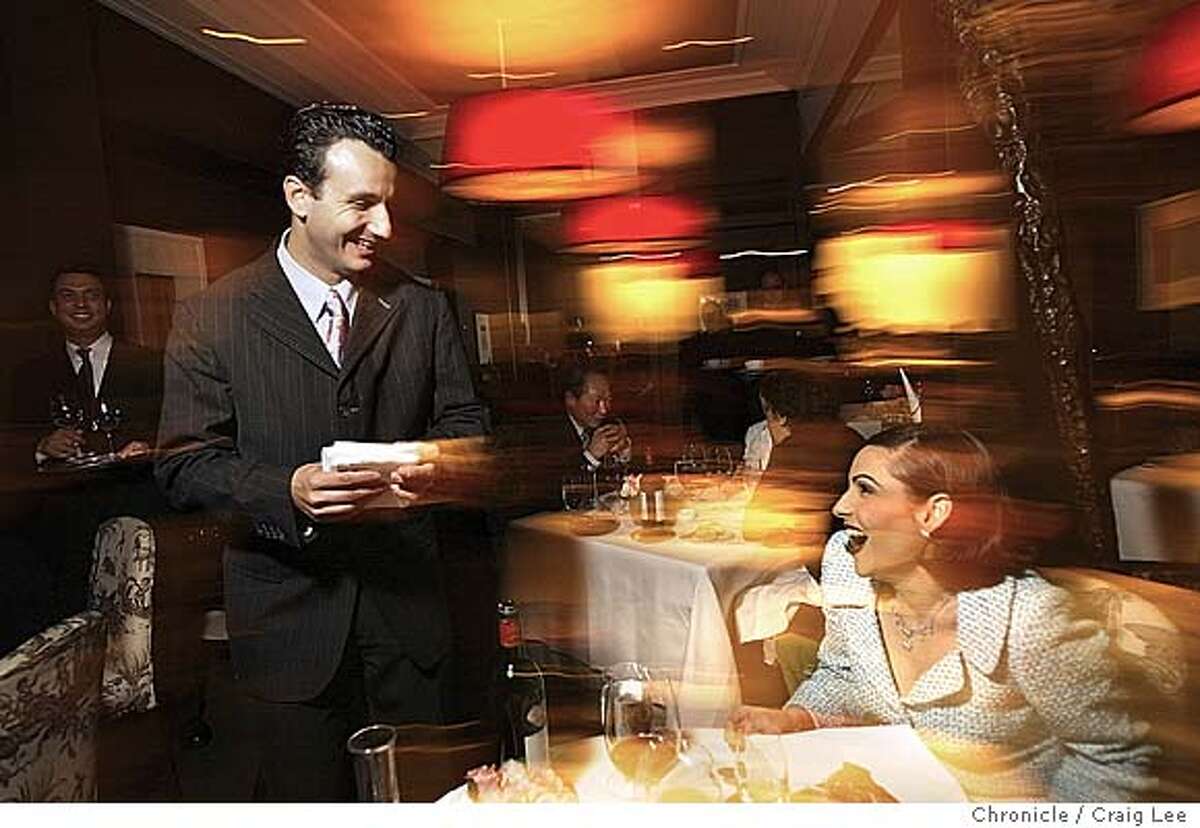

The front door of the restaurant leads you to the podium, where I stand sentry with at least one of my managers, a hostess, an Open Table reservation computer, and two phones that don’t stop ringing. To your right is a long L-shaped calacatta marble bar full of white men in their 50s leering at every woman of any age entering the restaurant, swilling martinis from our birdbath glasses, or double vodkas from Burgundy glasses as if dying of thirst. To your far right is the lounge, six low-top tables with soft chairs, an area I use strictly for walk-ins that remains full from 5:00 until closing most nights.

Past me is the long rectangular main dining room, which can fit two hundred, with a smaller thirty-seat private room all the way in the back. A hundred conversations echo off the walls and twenty-five-foot-high ceiling, mixed with a dated music mix that has become just white noise. The restaurant is halfway through a busy Friday night, during which it will feed about 450 guests. Outside, luxury sedans and SUVs that cost more than my annual salary fill the parking lot, a homogenous sea of white or silver cars, at least four of which bump into each other daily, in the eternal search for a parking spot closer than twenty feet from our entrance. The cops from the nearby precinct look out for me because I usually buy their meals when they’re on break, but they also know our lot is a target-rich environment for nabbing DUIs. Half of our regulars drive on suspended licenses anyway, repercussions are for poor small people.

“Good evening, Mr. Palermo,” I say, recognizing an attorney who might dine with his wife or his mistress, depending on the day of the week. Since it’s Friday, he’s here with Miss Salerno. Mrs. Palermo and the kids usually come wit him on Sundays. Palermo made his money suing various municipalities on Long Island as an ambulance chaser, and later founded a firm that litigated on behalf of those same municipalities. Our tax dollars at work.

“Danny,” the lawyer says, his lacquered teeth and manicured nails glimmering in the restaurant’s dim lighting. I hate that name when uttered by anyone other than two guys I grew up with, and even answer the phone as Daniel. Palermo shakes my hand, and I pull my hand away to stuff a folded twenty into my trouser pocket. Palermo never has a reservation, but I make them for him anyway, because his visits are as regular as his colon after a Metamucil. Miss Salerno smiles in our general direction.

I turn to Lisa the hostess, a college student who’s wide-eyed at the shenanigans of her town’s putative grownups. I’ve already had to warn a half-dozen dirtbags at the bar away from Lisa since she started, knowing that they have daughters older than her. “Table thirty-one for the Palermo party, please,” I say, a coveted corner of the long banquette that lines one of the walls. Lisa just nods, grabs two menus, and leads them away.

“Motherfucker,” Martin the manager mutters next to me, his Eastern European accent making his R’s roll. I couldn’t run this restaurant without Martin, who took my arrival in stride, even though the owners had considered him for the general manager position. There isn’t a player in this Long Island bedroom community that Martin doesn’t know, which is invaluable when we’re at the front. Then I see the motherfucker in question. It’s Mr. Merrick, he of the impressive height and a girth to match, longish gray hair that always looks a day past needing a shower, and about $20,000 in pinky rings. He does something related to real estate or mortgages, I never bothered to find out, and can’t even fathom that people would trust a guy with an affinity for velour track suits with their money. Like, did the Sopranos need a stand-in for Big Pussy?

“I can’t stand this clown either,” I say to Martin through clenched teeth. “Your turn, I dealt with him last time.”

“You owe me, bossman.” Martin gives Merrick a huge, fake, obsequious smile. “Welcome back, Mr. Merrick, good to have you.” Merrick is trailed by a smaller younger clone of himself, an older blonde lady whose boob job and facelift look like they should be insured by Lloyd’s of London, and a sullen teenage girl whose glare at her father’s back could freeze milk.

No hello, and more importantly for Martin and me, no handshake. Strike one, Merrick. “There’s four of us,” he says in that faux-Long-Island-guido-tough-guy accent that makes me want to pierce my own eardrums with chopsticks. Yes, thank you, we can count.

Martin maintains the charade. “What time is your reservation, Mr. Merrick?”

“Don’t need one, I’m playing golf with the owners tomorrow morning.” Ahm playin gawlf wid the ownahs tuhmawrra mawnin. Jesus wept, I have non-native-born employees here who speak better and clearer English.

I step in. “If the owners had just called ahead for you, I’d have saved you a table.” I make a show of looking at my watch while Martin retreats to the coat closet to keep from laughing. “Give me about twenty or thirty minutes.”

He gives me a look my five year old might give me after I take his cookies away. “But I wanna sit down right now.” Impatience? Sense of entitlement? A swing and a miss for Merrick, strike two.

“I haven’t got a table for the folks who do have a reservation.” The owners do, in fact, enjoy how I push back with some of our regulars, who believe that their excrement is not odiferous. I followed the owners’ example, glad handling but digging into an untapped and surprisingly deep reservoir of passive aggressiveness. “Please, wait by the bar, I’ll let you know.” And kindly get your complimentary case of kiss my big Korean ass while you’re there.

The Merricks retreat to the bar, where Martin tells the guys to put the Merricks’ drinks on the owners’ comp check. Ernesto the bartender slips me a rocks glass with two fingers of Jameson, which I gulp down quickly, then head back to the podium. The next guy speaks before I even turn to face him, because I’m expected to be clairvoyant. “I’m Mistah —”

“Huntington,” Martin finishes for him, and shakes his hand. Martin gives me a look, there was money in the handshake, then points his eyes down at a panting furry rodent in a ridiculous little stroller. “Mr. Huntington,” Martin says, “you know you can’t bring the dog in here.” Mrs. Huntington, pushing the stroller, looks like she might gouge our eyes out with her car keys.

“She won’t bother anyone. Just bring us a bowl.” Yeah, no. Last I checked, we don’t have nourriture pour chiens avec demiglace on our menu, and the Huntingtons had already made the mistake of admitting their rodent isn’t a service animal, which I do allow. I let Martin continue to work on Huntington while I help Lisa answer the incessantly ringing phones.

“Thank you for calling The Restaurant, this is Daniel, how may I assist you?”

“I need a table for five people in about half an hour.”

“Earliest I can do that is ten o’clock, otherwise we are fully booked.”

“What if I showed up now?”

“Then I’ll put you on the wait list, but not until you physically arrive. I can’t speak to how long the wait might be, though.” Because my middle name isn’t goddamn Nostradamus. Click.

“Thank you for calling the Restaurant, this is Daniel, how may I assist you?”

“David! It’s Marty!” Who? I’m already not doing anything for this guy if he can’t get my name right after I just identified myself two seconds ago. Marty, last name and face unknown, expects me to miraculously shit him a table — like the Immaculate Conception, but for Maître d’s — when I have a long enough wait list physically in the restaurant, most of them waiting patiently. “Nothing sooner?” No, I just get a kick out of the schadenfreude. Click.

I transfer the next call to the bar for takeout, and check the next guests in. A younger couple, younger for this town meaning not born before the Johnson Administration. She has the lean, hungry look of a bored Long Island housewife who spends most of her day doing yoga or spinning while studying for the realtor exam; he has the pallid, fleshy look of someone who spends way too much time in a Midtown office, pushing tidy piles of paper from one side of his desk to the other. They give me their name, I send them off with Lisa, and instantly forget them.

Mrs. Jones, arguably the den mother of the ladies who lunch and do yoga and go to spin class. Always a party of six, including four kids who barely acknowledge their parents’ existence except as chauffeurs. Of course you’re forty minutes early. Of course I still don’t have the table ready for you yet, because reservations work on other diners’ schedules, not yours. She says she’ll walk around, but make sure I call as soon as the table as ready. Otherwise, she’ll just be back in forty minutes. She’s a pill, but not always, and she did just hand me a ten, so I decide we’ll call. Maybe in thirty minutes.

Problem. Lisa hurries back to the podium with a few updates — who’s on dessert, who’s paying their check, who’s camping out — and a stack of menus clutched to her chest. I feel bad for the kid, who until two weeks ago had no idea what her neighbors — or, rather, her neighbors’ parents — are truly like. “Dan,” she says, “that couple doesn’t like the table. She yelled at me.” Don’t cry up here, kid, keep it together for fuck’s sake. I hand her the keys to my office, tell her to man the phones from downstairs, and get Erik up here. Erik is another of my managers with an accent of debatable provenance, one of those Mediterranean islands that always seems to either be a vacation hot spot or terrorist target. On busier nights, he’s my eyes in the dining room, but with a hostess on the verge of tears, I need him more as my other bookend opposite Martin.

Erik ambles up front, he’s so damn tall he could play center for the Maltese national basketball team if they had one. He looks like a blonde square-jawed Aryan recruiting poster, but claims that everyone in his family fought the Nazis as partisans during the war. What matters more for me is that he’s a classically trained waiter who came up to management years ago like Martin and me, and is utterly unflappable. One irate guest had recently told Erik that her party’s dinner was a disaster. “Madame, the Middle East peace process is a disaster. This is just dinner. How can I fix this for you?”

I leave the podium to deal with the complainers, who are standing next to table 41, a small rectangular table for two along the banquette wall, not a more intimate square table in the back where they can sit catty-corner to each other. Is it our best table? Not by a long shot, Palermo and his side piece are sitting there, but it’s hardly our worst. The husband speaks up while I’m still fifteen feet away and can still barely hear him over the crowd noise. “Listen, pal, I’m not gonna spend two or three hundred dollars tonight just to be shoved up against other people like this.”

The reply escapes me before my internal censor can keep up. “The guests on either side of you don’t seem to mind. We actually provide more space between tables on the banquette than [two of our competitors].” Okay, shit, I hadn’t wanted to say that, but in for a penny, in for a pound. If I back down now, the guests will see that as weakness and take advantage of it on their next visit. No mercy.

The wife taps him on the elbow, and I can just about intuit the husband’s next words. He even stands straighter as he says them, but I’m 6-foot-3 and not intimidated in the least by unarmed men. “You obviously don’t know who I am.”

It is definitely no-mercy time. “Yes, I do know you are,” I lie like a rug. “But I’ve also got two CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, a CNN legal analyst, the owners’ daughters, and the managing partner of a billion-dollar hedge fund dining here.” This is only partly a lie, the hedge fund guy has a reservation tomorrow, and the owners’ daughters left an hour ago. “Forgive the Orwell reference, but some animals are more equal than others, especially during a busy Friday dinner service.”

Pudgy man slouches ever so slightly, and I know I’ve won, but I decide to let him off gently. “If you’d requested a standard square table, I can always try, but I can never guarantee it. One of those will probably be available in fifteen minutes or so. Can I buy y’all a drink in the meantime?” That’s my other tool to throw people off, “y’all” is not a word often heard north of Maryland, and for damn sure not east of the Gowanus Canal. Pudgy man looks at his wife and shrugs as if to say, I tried, and I lead them to the bar. Behind us, busboys push two of the banquette tables together for the Merrick party. Merrick gives me a nod as he passes me — this could mean anything from thank you to go fuck yourself, I can’t bring myself to give one-third of a fifth of a shit. I stop by the bar, where Ernesto rewards me with another whiskey.

“Nice job,” Erik says, a satisfied grin on his chiseled face. “I would have made them stay there, though.” He would have, too, the soulless bastard. Then he and I turn to face The Douche. He’s a Thursday/Friday regular, usually at the bar, and is convinced with the conviction of a saved evangelical that all women want him, a taller version of Bob Hoskins’ character from Who Framed Roger Rabbit. His real name is George, and he owns car dealerships without which these townspeople would wither: Mercedes, Jaguar, BMW, Land Rover. My and Martin’s down-market but far more dependable Japanese hatchbacks look grubby in comparison in the parking lot.

The Douche is in full regalia tonight: an untucked striped shirt that strains against his belly, sleeves rolled once to show off the contrasting inner cuff, gold chains and Amazon rainforest of chest hair displayed by unbuttoning the top three buttons of his shirt, and sunglasses even though it’s almost 9:00. He’s by himself, but assures Erik that three ladies will be joining him shortly. Erik shunts him to the bar until The Douche’s ladies arrive, and we watch in horror as The Douche uses the olives in the bar’s garnish tray like a personal salad bar. Ernesto now has to discard everything in the garnish tray, then cut fruit and spear olives in the middle of the dinner rush.

Martin says what’s on my mind. “The odds are, he’ll drop his coke in the men’s room, a busboy will find it later, and we can sell it back to him next week. The girls will leave him because he can’t find his coke, so he’ll get drunk and try to start a fight.”

“Christ, I hope you’re wrong,” I say, because no one who doesn’t run a nightclub needs that kind of drama. Lisa is doing yeoman’s work downstairs, juggling four or five calls at a time, only intercomming us if she has a question, and her voice sounds more even. I wonder if she’s rifled through my desk and found my flask, it could do the kid a world of good.

Erik greets the next couple, whom he recognizes as regulars of our sister restaurant down the street, where he worked before transferring here. And of course the couple doesn’t have a reservation. Why should they? “Call your sister restaurant,” the guy says, without making eye contact, which I hate down to my bone marrow. “They know me there. He does, too.”

“Erik knows you,” I say, “but here, you don’t have a reservation.”

“Come on,” he pleads, because I dared to call his bluff, and sees that Erik defers to me.

“The wait without a reservation is about an hour,” I say, and watch while his face collapses into layers of jowls. “If they know you at our sister restaurant, they might get you in over there, but here it’s gonna be an hour.” The couple reluctantly places their name on the waitlist, and squeeze past a dozen people because by now the bar is standing room only.

I’m suddenly exhausted, and tell Martin and Erik to cover for me while I sneak out back for a smoke. The unspoken agreement is that Martin will poison himself next, then Erik. I glide through the dining room, ignoring Palermo’s wave, Merrick’s inscrutable nod, Mrs. Jones’ wagging fingers, through the swinging doors and into the kitchen. Chef, yelling orders to his cooks, the back of his head covered in sweat in the hundred-degree sauna, doesn’t even see me, which is for the best.

Out back, which smells exactly like the loading dock of a restaurant should, a miasma of rotting food and deck cleaner, I lean against the wall and inhale carcinogens deep into my lungs. It’s blissfully quiet here, no phones, no people, just me and my cancer stick. To be perfectly honest, I don’t need the cigarette, but I’ve been addicted since the Reagan years and this is the only plausible excuse I have to leave the front during service. I rub my eyes, which are tired from staring through dim lighting at the reservations computer and people under the mistaken impression that I like them.

I walk towards the front of the restaurant, realize that the crowd waiting to be seated has thinned, and I can even see a few empty tables as we enter the downslope of dinner service. I give Erik a head bob and hand him the stash of folded and crumpled bills from my trouser pocket. Martin does the same, and Erik disappears into the coat room for a few minutes. Erik hands me my share of the door tips, and tells me he’s giving Lisa a half-share. I have no problem with that, and tell the boys I’m leaving after a thirteen-hour day.

“See you tomorrow, boss” Erik says, and I just give him a look. Back to the salt mine tomorrow.